8月 29 2019

電気機械試験|パワートレイン試験|HBM

続きを読み取る

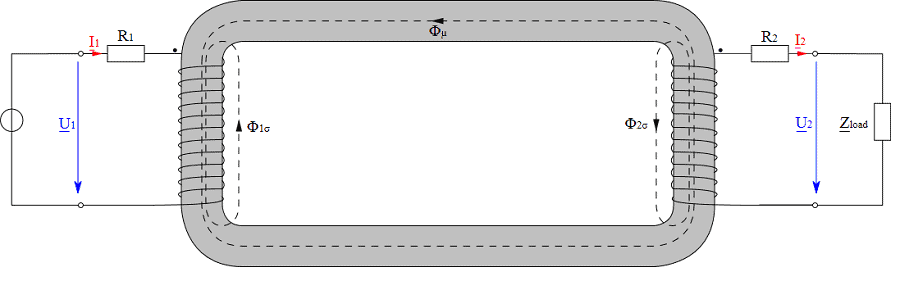

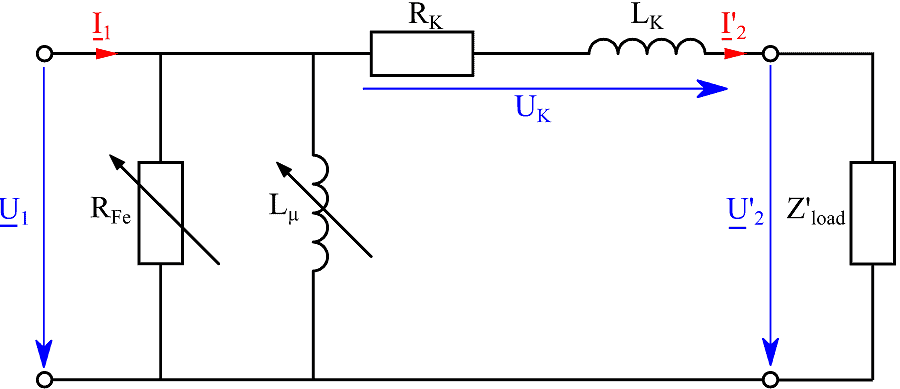

Used in many different applications, the transformer is one of the most important components in alternating current technology. It is used in electrical energy technology to transform between different voltage levels. To ensure efficient transmission of energy in this case, good efficiency and optimum utilization are required.

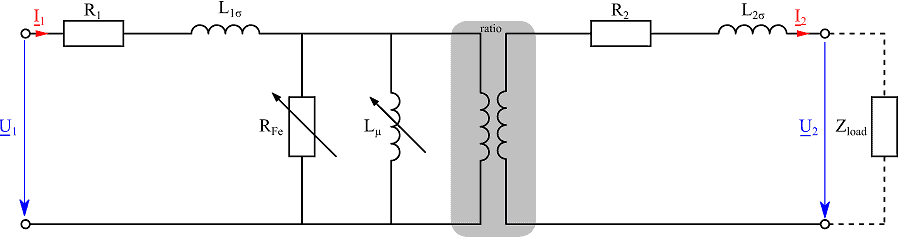

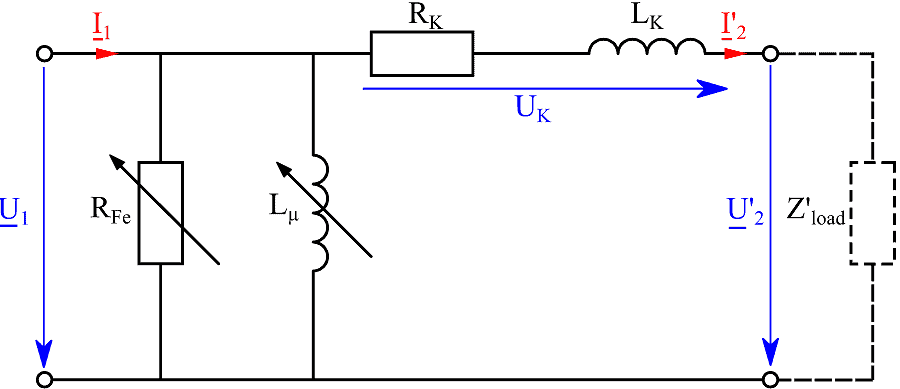

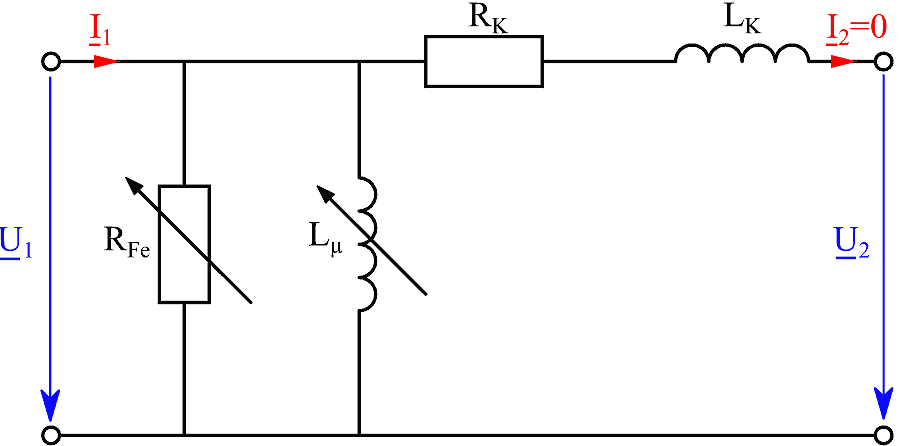

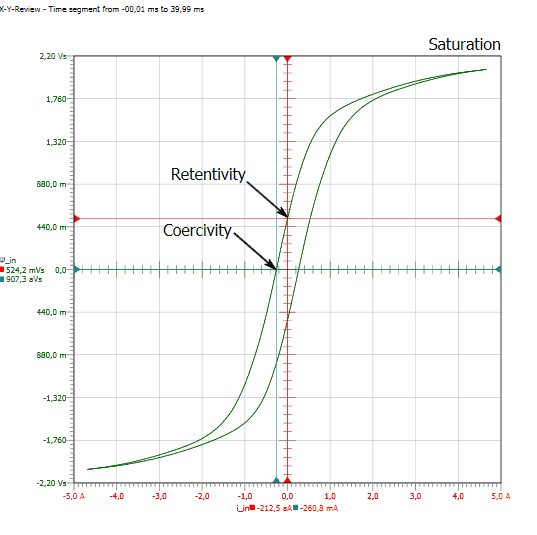

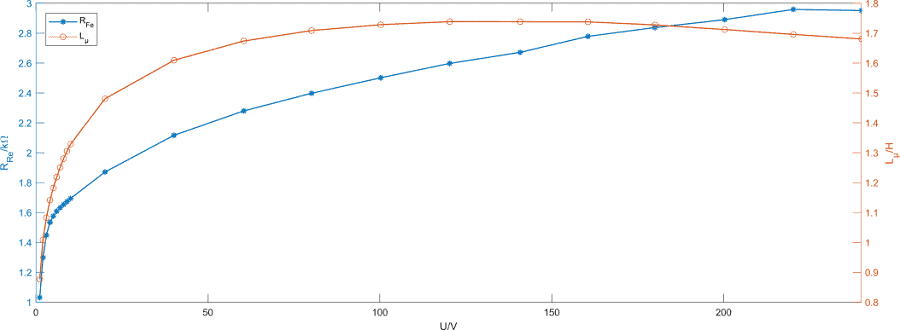

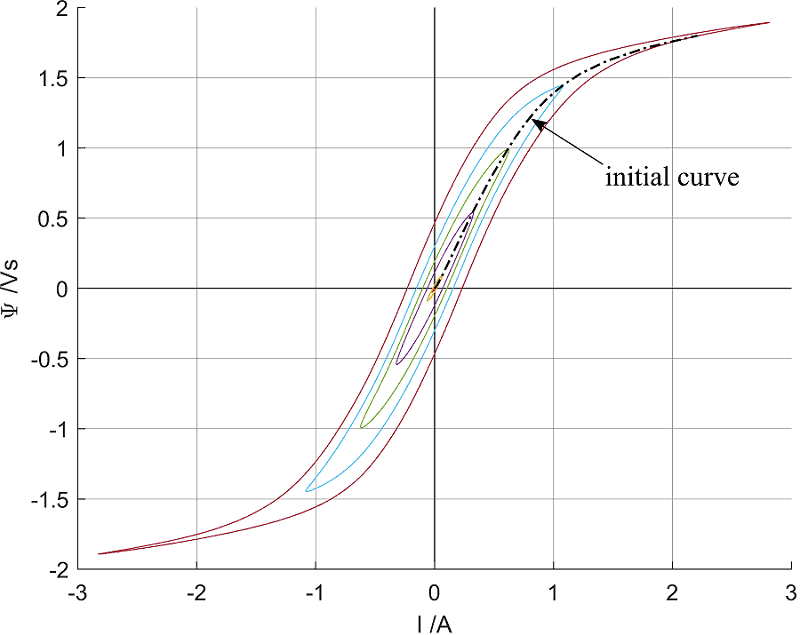

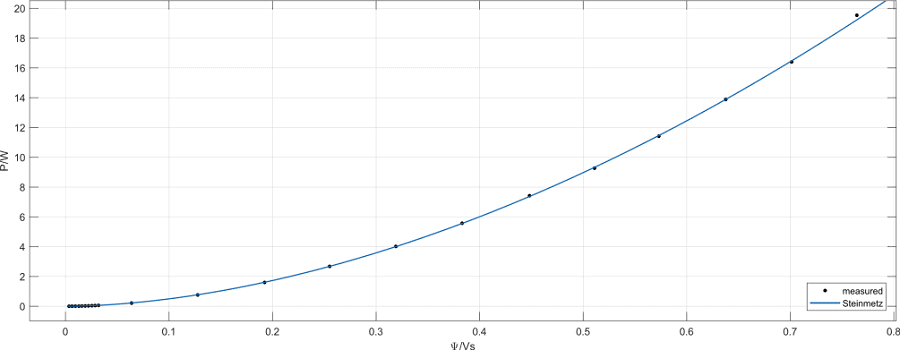

Despite the wide prevalence of power electronic circuits, the transformer is also still required for small power supplies to allow for the required galvanic isolation. It is used in measurement technology to convert measured quantities. Transformers must meet different requirements depending on the intended use. Adaptations to these requirements can be made through the selection of the core material that is used and by varying the geometry of the core. The individual properties of a transformer can be represented by a simple equivalent circuit diagram. This can be used to evaluate how suitable a transformer is for a proposed application and its behavior at various load points. In this article the equivalent circuit diagram of the transformer is first derived and explained. Next measurements and calculation methods for determining the equivalent circuit diagram and the loss of iron in the transformer core are presented. The measurements and calculations are performed with the HBM Gen3i data recorder. The appendix contains all the necessary formulas and they can be imported into Perception.